◖The Curious Case of Winged Genitalia◗

Throughout history, the depiction of winged genitals in art has been more common than one might expect. But why exactly did ancient civilizations adorn their phallic and yonic symbols with wings? Was it a deeper cultural or religious significance, or did our ancestors simply have an unexpectedly playful sense of humor? Phallicism and Yoni worship have been integral to many cultures in South Asia since the Vedic period. In India the female genitalia, revered as the Yoni, symbolizes divine feminine energy, while the male counterpart, known as Lingam, represents creation and masculine power. But where do the wings come in?

The Roman God of the Winged Phallus

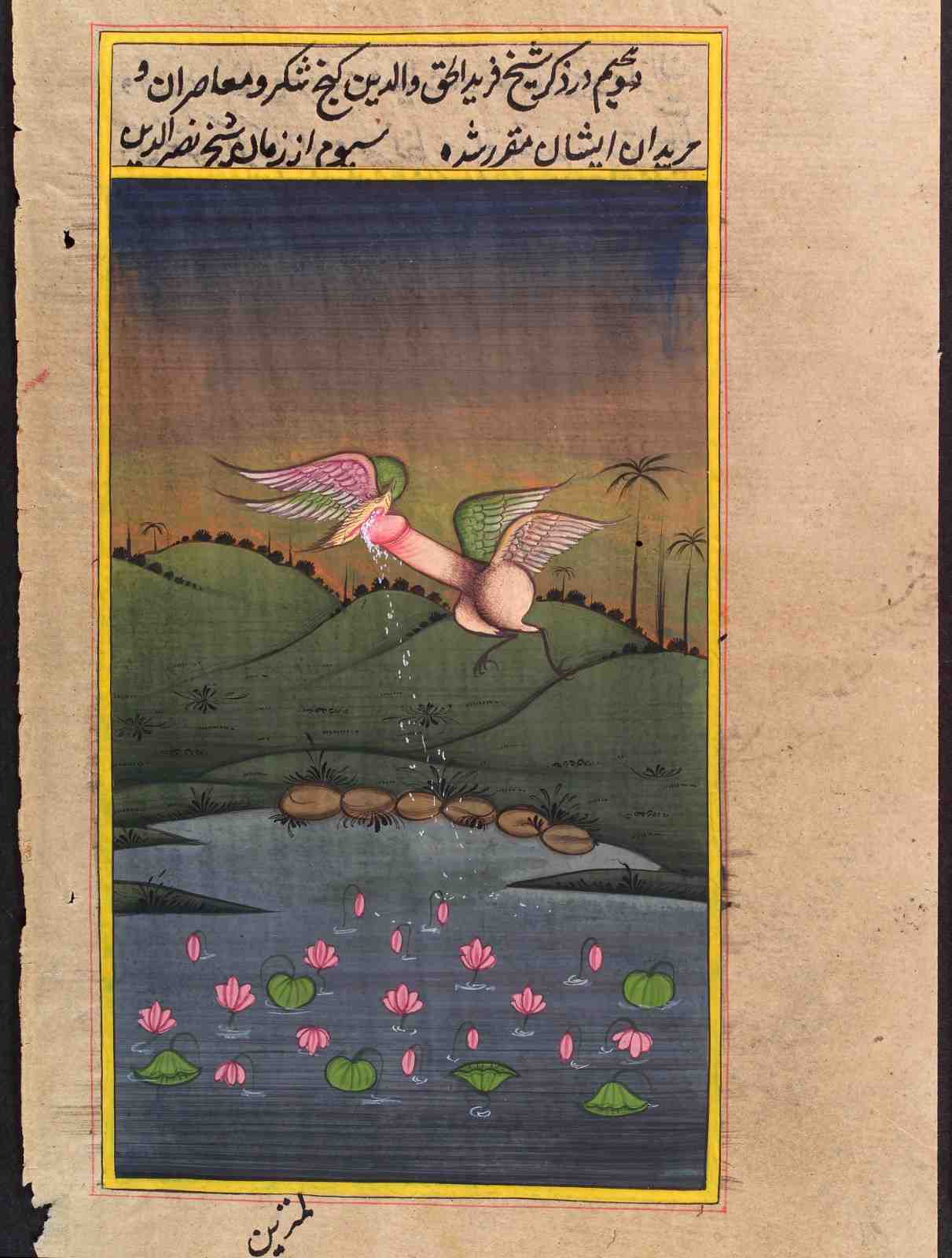

In Ancient Rome, the answer lay in the worship of Fascinus, the winged penis god. Among the vast pantheon of Roman deities—over 200 in total—Fascinus held a special place as the embodiment of masculine regenerative power. His symbol? An erect penis, complete with testicles, legs, and wings (Fig.1)—allowing him to soar across the skies, bestowing blessings upon fortunate mortals. Both the Greeks and Romans believed Fascinus to be apotropaic, meaning he had the power to ward off evil. His likeness was worn as amulets, pendants, and wind chimes, hanging from the necks of devoted worshipers for good luck and protection. Roman art and mythology often feature stories of sleeping maidens waking up to find that Fascinus had paid them a nocturnal visit—an unsettling notion by today's standards. However, with the rise of Christianity, Fascinus and his winged phallus fell out of favor, vanishing alongside the pagan deities of antiquity.

Echoes of the Winged Phallus in Medieval Art

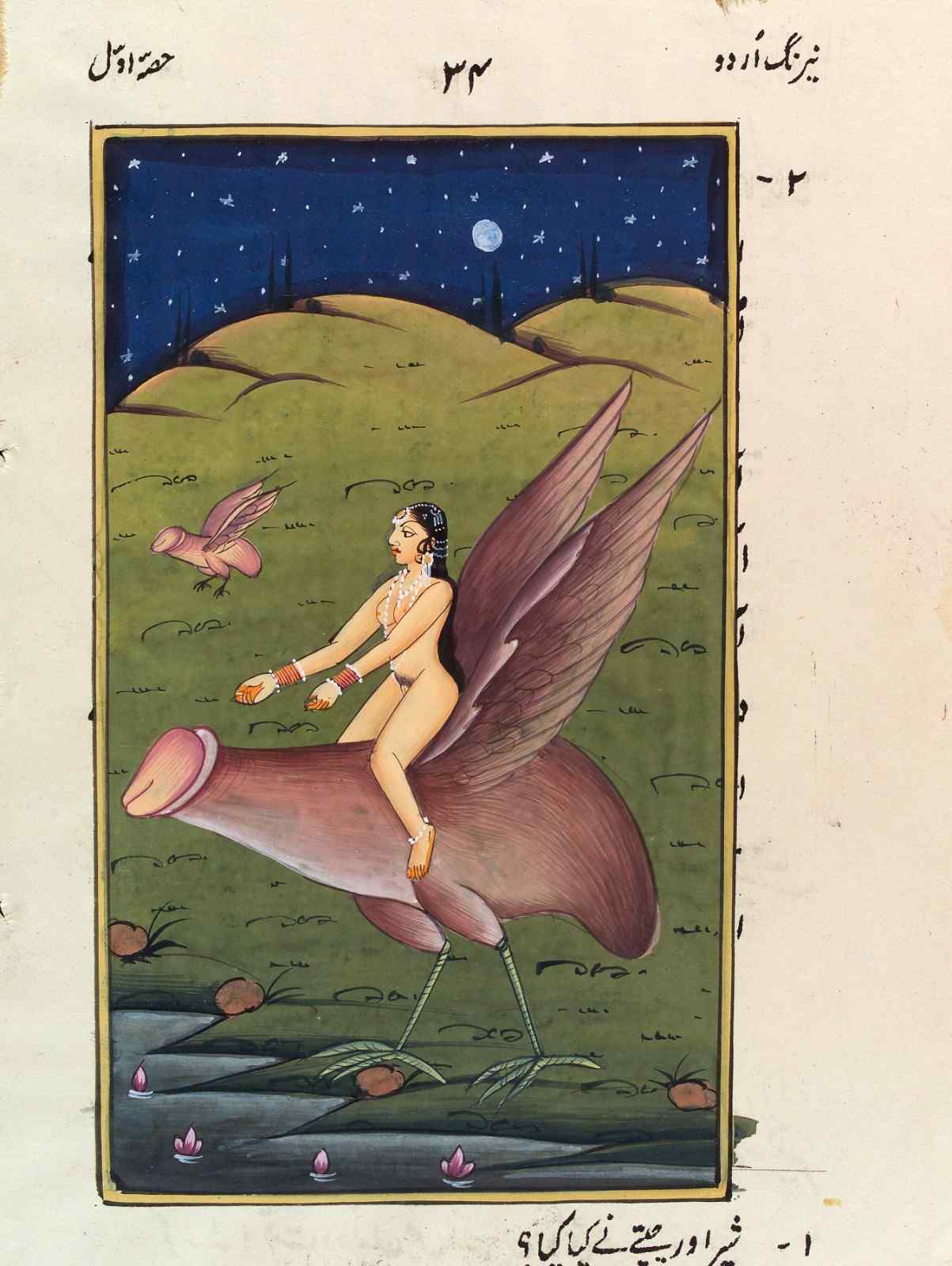

Though Fascinus faded from mainstream religious practice, imagery of winged and legged genitals continued to appear in artistic and cultural expressions across different eras. Post-Christianity, etchings from the Middle Ages depict witches at Wiccan sabbaths, riding winged or legged penises alongside demons and devils (Fig.2). The monster in the print on left has been transformed from a phallus in the print on right. Picart's print appeared in 'Impostures innocentes', published by Picart’s wife in 1734, two years after Picart's death. Strikingly similar theme appears in a miniature painting from India, where a richly adorned woman—likely a queen or princess—is shown riding a giant winged phallus against a lush natural backdrop. The artist may have been recreating a scene akin to a Wiccan gathering or engaging in subtle satire.

In Hawaiian mythology, there is a powerful goddess named Kapo, known for her extraordinary ability—she could detach her vagina and send it wherever she pleased, only to have it return to her. One day, Kapo’s unique gift became a tool of salvation. Her younger sister, Pele—the fiery goddess of volcanoes—was wandering through the valleys when she realized she was being stalked by Kamapuaa, the half-man, half-pig god. Kamapuaa had long desired Pele, and seeing her alone, he seized the opportunity to force himself upon her. Pele resisted with all her might, but she could not escape. Desperate, she cried out for her sister’s help.

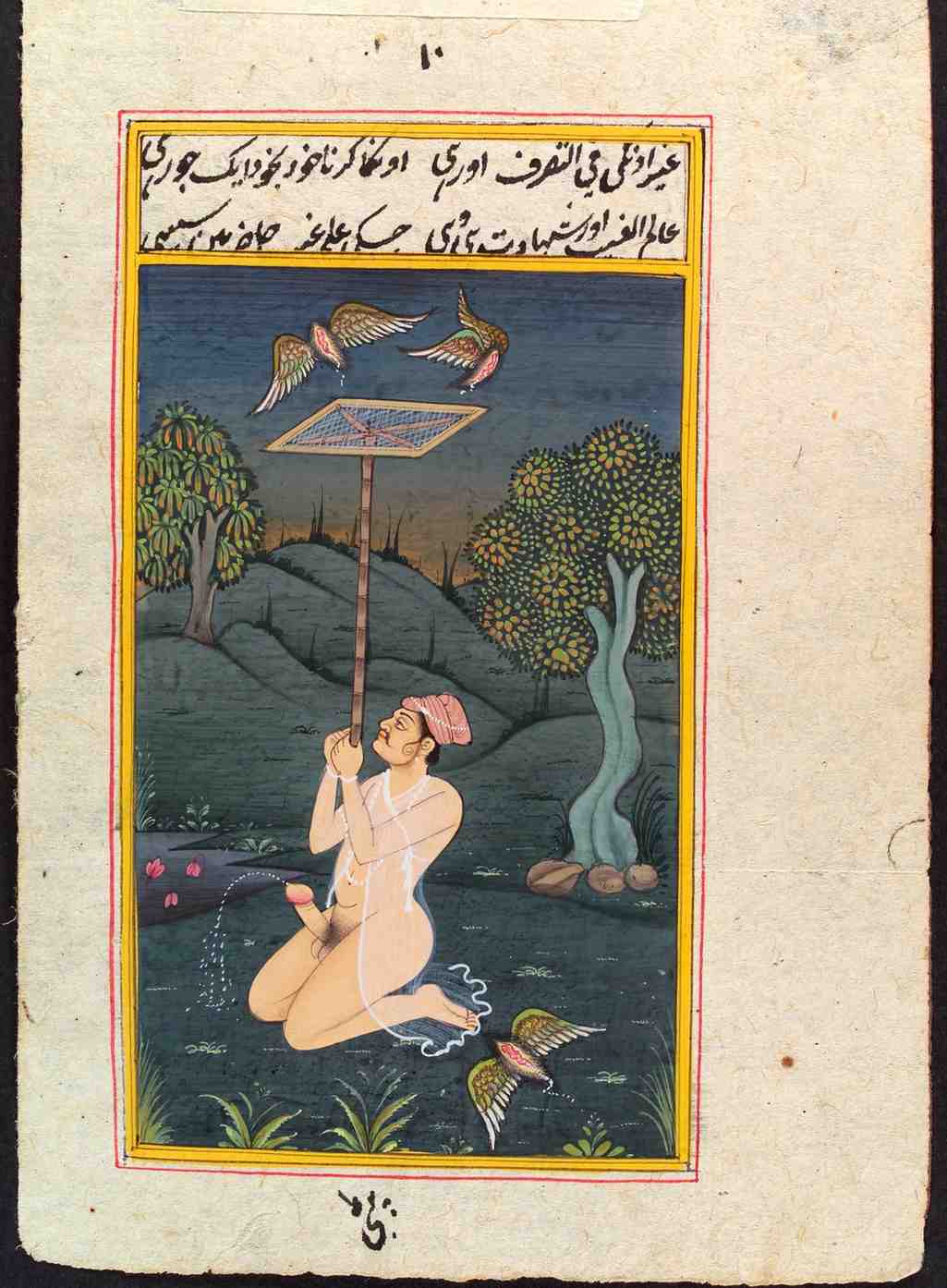

Hearing Pele’s plea, Kapo acted swiftly—she detached her vagina and sent it soaring through the air. The unexpected sight stunned Kamapuaa, who immediately abandoned Pele and began chasing the flying vagina instead. Entranced, he pursued it across valleys, over borders, and into distant lands. The enchanted organ eventually crashed into a mountainside, leaving behind a massive imprint on the rock before returning to Kapo. Meanwhile, Kamapuaa, realizing too late that he had been deceived, found himself exiled in the barren wilderness. Interestingly, this imagery of flying vaginas appears in miniature paintings from India as well, where they depict men capturing winged vaginas or engaging in surreal, otherworldly unions with them. These striking visual parallels suggest a shared fascination across cultures with myths of disembodied sexuality and divine trickery.

In some Renaissance-era prints, a blindfolded Cupid is seen riding a winged penis, possibly a satirical commentary on love, lust, and fate. These bizarre and whimsical depictions raise the question—were they purely symbolic, meant to critique societal norms, or simply a testament to the enduring fascination with fertility and the erotic? Regardless of interpretation, these fantastical, airborne genitals serve as a reminder that history is full of surprises, humor, and symbols that often transcend time.

Text by Museum of Eroticism

Image Courtesy: National Archaeological Museum in Athens, The Trustees of the British Museum, Wellcome collection.

References:

1. Clarke, R. John. Looking at Lovemaking: Constructions of Sexuality in Roman Art, 100 B.C. – A.D. 250. University of California Press, 2001.

2. Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Penguin Press, 2009.

3. Friedman, M. David. A Mind of Its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis. The Free Press, 2001.

4. Why Are Ancient Greek Phalluses Funny? (getty.edu)