◖Debra Paget’s Forbidden Dance: The Western Gaze, Orientalist Fantasy, and the Costume that Defined Exoticism◗

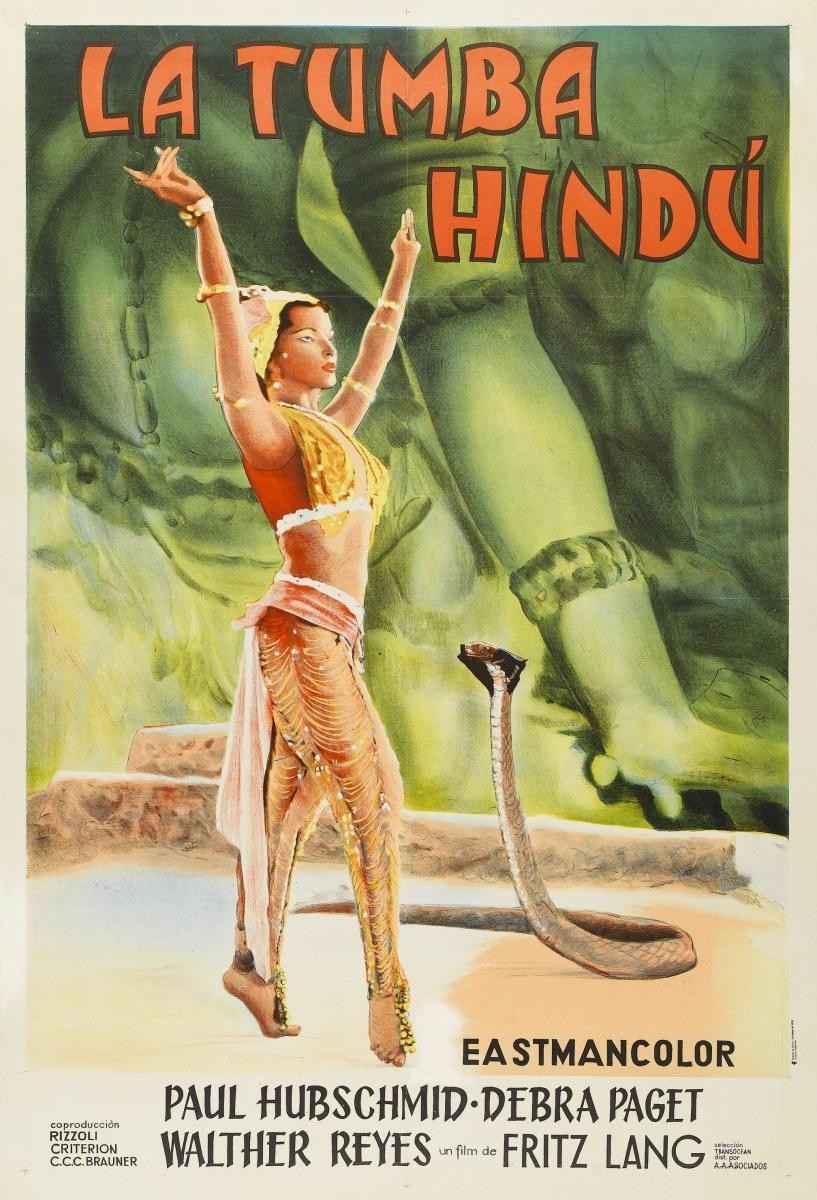

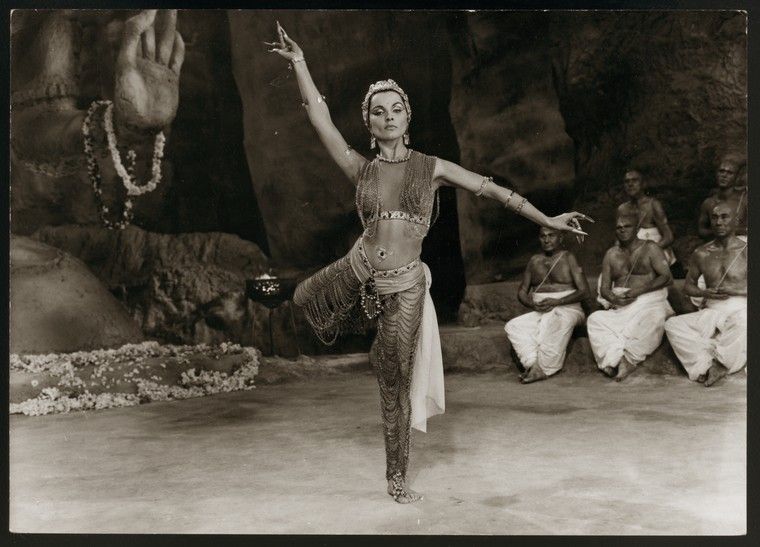

Few moments in classic cinema are as hypnotic and controversial as Debra Paget’s snake dance in The Indian Tomb (1959). Dressed in a revealing, skin-tight, jewel-adorned costume, her performance became one of the most sensual yet problematic depictions of Eastern mysticism through the lens of Western cinema (Fig.1). Designed by Claudia Hahne-Herberg and Günter Brosda, the outfit was a striking blend of fantasy, eroticism, and exoticism, all wrapped in the seductive aesthetics of the Western Orientalist gaze. Beyond its visual spectacle, this performance speaks volumes about how the West romanticized and eroticized Eastern cultures, reducing indigenous traditions into fetishized fantasies for white audiences.

The Making of an Iconic but Problematic Costume

For her role as Seetha, a temple dancer, Paget’s costume was designed to evoke sensual mysticism, though it bore little resemblance to real Indian temple dance attire. Hahne-Herberg and Brosda’s design was a daring creation, carefully constructed to toe the line between acceptability and scandal. Sheer, flesh-colored bodysuit was made from a fine mesh or silk material, designed to mimic nudity while technically covering her body to comply with censorship standards. Gold embellishments and sequins were placed strategically to highlight curves, similar to Western interpretations of harem outfits and belly dance costumes. Intricate beadwork and metallic embroidery inspired by Southeast Asian dance attire rather than authentic Indian clothing. Golden jewelry and headdress borrowing aesthetics from Egyptian, Thai, and Persian influences, further proving how Hollywood's version of “India” was an eclectic blend of Eastern cultures rather than an authentic portrayal. While the outfit was meant to symbolize temple dance mysticism, its true purpose was clear: to present the female body as an erotic object, wrapped in an illusion of cultural legitimacy.

The Dance Scene: Eroticism in Motion

The snake dance in The Indian Tomb is a fever dream of sensuality and submission, deliberately crafted to heighten Western fantasies of the East. As Paget writhes and undulates before a massive stone idol, her movements mirror that of a seductress rather than a traditional dancer. Unlike authentic Indian classical dance—where storytelling, mudras (hand gestures), and expressions play a vital role—Paget’s performance is purely about physical allure (Fig.2). This reduction of Eastern spiritual practices into sexualized spectacle reflects a long-standing Western tradition. Stripping indigenous cultures of their depth and reducing them to visual stimuli for pleasure. Reinforcing the idea that Eastern women exist to be seen, adorned, and conquered. Emphasizing nudity as inherently sexual, despite historical depictions of nudity in Indian art being spiritual rather than erotic. Paget herself was likely a passive participant in this construction, simply playing the role crafted for her. However, the film’s director, Fritz Lang, and its predominantly Western production team were responsible for shaping this hyper-romanticized version of India, designed for European and American audiences hungry for exotic fantasy.

The Western Gaze: Eroticizing and Othering the "Orient"

Hollywood and European cinema have long viewed the East as an eroticized paradise, full of sensual women, mysterious men, and sacred rituals turned into spectacle. The Indian Tomb was part of a long tradition of Western Orientalist cinema, which included films like:

Princess of the Nile (1954) – Paget herself starred in this over-the-top fantasy of Egypt, which bore little resemblance to actual Egyptian culture.

Salome (1953) – Where Rita Hayworth’s seductive “Dance of the Seven Veils” became a symbol of biblical eroticism.

The Sheik (1921) – A film that romanticized white women being "tamed" by powerful Middle Eastern men, reinforcing colonial fantasies.

This obsession with the East as a realm of sexual liberation was rooted in colonial-era views, where indigenous cultures were seen as primitive, exotic, and uninhibited. The nudity in Indian art and dance traditions, which was once a form of divine expression, was twisted into Western ideas of licentiousness and submission. While Indian sculptures of celestial dancers and apsaras (divine maidens) celebrate grace, fertility, and artistic beauty, Hollywood adapted these images into titillating, submissive figures meant for male conquest.

Redefining Sensuality: The Impact of Paget’s Performance

While The Indian Tomb reinforced many problematic tropes, it also redefined sensuality in Western cinema by:

Pushing the limits of censorship – Paget’s near-nude costume and intimate choreography influenced later pop culture moments, including music videos, stage performances, and fantasy films (Fig.3).

Challenging traditional Western femininity – Her performance stood in contrast to the demure and passive female characters of the 1950s, paving the way for more powerful, seductive female roles (Fig.4).

Creating a cult classic – While the film was ignored in Hollywood, European audiences embraced its boldness, and it later became a cult favorite for film and fashion historians.

Despite its artistic appeal, the film remains a case study in how the Western gaze distorts indigenous cultures—an issue still prevalent in media today.

Between Art and Appropriation

Debra Paget’s snake dance remains one of the most sensual moments in classic cinema, yet it is also a textbook example of Western exoticism and sexualized Orientalism. Her costume, choreography, and character were designed not to represent India, but to indulge a Western fantasy of it (Fig.5). Today, as we continue conversations around representation and cultural authenticity, films like The Indian Tomb remind us how much of the past was shaped by colonial perspectives on beauty, sensuality, and race. While Paget’s performance is visually unforgettable, it’s crucial to recognize that it is less a tribute to Eastern dance and more a reflection of how the West has historically viewed the “Other” as a beautiful object to be gazed upon.

Text by Museum of Eroticism

Image Courtesy: IMDB, Film Affinity US, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

References:

1. Said, Edward. Orientalism. Pantheon Books, 1978.

2. Steele, Valerie. Fetish: Fashion, Sex & Power. Oxford University Press, 1996.

3. Vijayakar, Rajiv. Bollywood’s Dance Culture: The Global Influence. HarperCollins, 2019.

4. Mulvey, Laura. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen, 1975.

5. Fritz Lang’s The Indian Tomb (1959) – Film Analysis from Criterion Collection & IMDb.